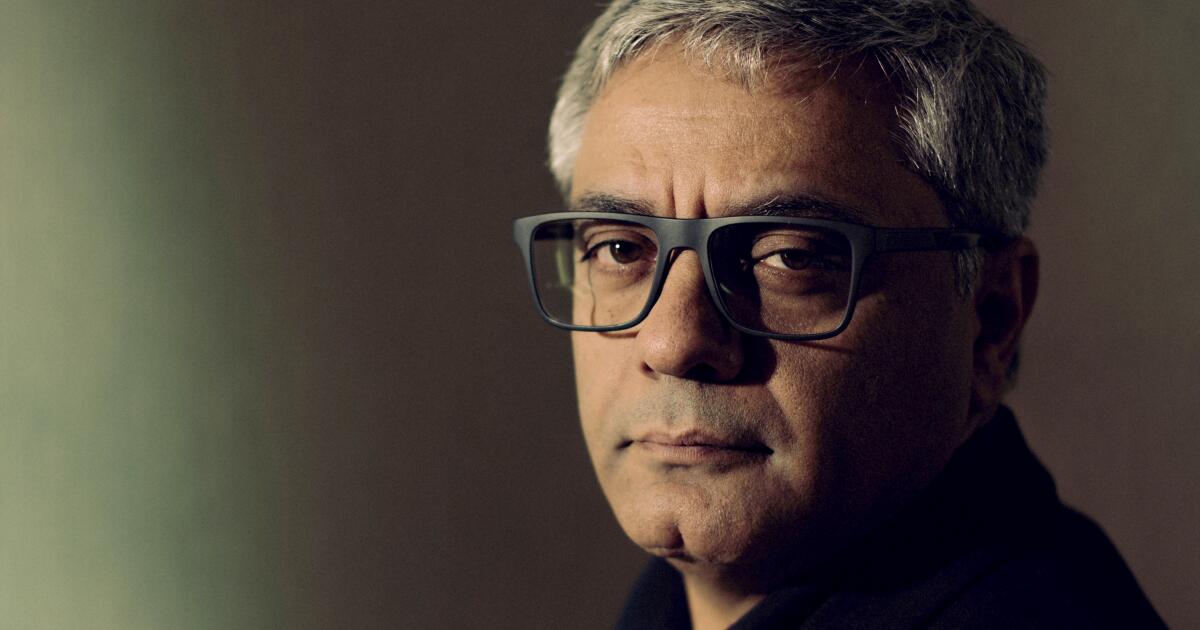

About half an hour into my dialog with exiled Iranian filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof, he receives tragic information from his dwelling nation.

Kianush Sanjari, a journalist and activist with whom he had hung out in jail, dedicated suicide by leaping from a constructing. “He perceived his physique as his solely weapon of protest,” the visibly upset director tells me by means of an interpreter whereas sitting within the empty restaurant of a West Hollywood resort.

He takes a second to compose himself. I ask him if we must always reschedule, however he decides to proceed with the interview. Overcoming the unthinkable has develop into a necessity.

Over the years, Rasoulof, 52, has been a recurring goal of Iranian authorities as a result of content material of his movies, which expose the Islamic authorities’s violent repression, which permeates all points of its residents’ lives. Since 2010 he has been convicted a number of instances, banned from making movies and spent a number of durations behind bars.

To keep away from a latest eight-year jail sentence, together with flogging, Rasoulof fled Iran in May after the regime requested him to withdraw his newest drama, “The Seed of the Sacred Fig,” from the Cannes Film Festival. which he had filmed in secret. Film Festival, the place he had been chosen to compete. He refused to obey and left.

After a treacherous journey on foot by means of an unknown route over the mountains, adopted by quite a few stops over the course of 28 days, he lastly made it to security in Germany. His movie is now the nation’s Oscar nominee for worldwide cinema.

Rasoulof, who now has German journey paperwork, was deeply touched by the German committee’s resolution to pick out his movie. “They merely selected to take heed to the world,” he says. “It’s an enormous gesture of assist for all filmmakers working below duress.”

In “The Seed of the Sacred Fig,” set within the midst of the real-life 2022 protests sparked by the dying of younger pupil Mahsa Amini whereas in police custody, the corrosive Iranian state authorities divides a household throughout ideological traces. Called by the federal government to behave as an investigating decide, Iman (Missagh Zareh), a lawyer, is pressured to signal dying sentences. Injected into the unrest by way of social media, his two younger grownup daughters, Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and Sana (Setareh Maleki), refuse to stay silent.

“Over the final 15 years I’ve had lots to do with Iran’s interrogations, censors, justice system and safety equipment,” Rasoulof says. “And I noticed commonalities amongst all these totally different individuals. What all of them shared is their submission to energy.”

From left, Mahsa Rostami, Missagh Zareh and Setareh Maleki within the movie “The Seed of the Sacred Fig”.

(Neon)

It was the expertise of his first function movie, 2002’s “The Twilight,” that sparked Rasoulof’s career-long dedication to dissident artwork. That movie, a docufiction about an inmate who will get married whereas nonetheless serving his sentence, confirmed individuals taking part in themselves, recreating actual conditions that they had skilled.

During that filming, Rasoulof spent just a few days in jail together with his actors, by no means imagining that he himself would return as an inmate just a few years later. “I could be the one director who has skilled so many alternative methods of being in jail,” he says, laughing. “Not solely as an observer, but additionally as an actual prisoner. They are fairly totally different.

At the time, Rasoulof, then in his early twenties, nonetheless believed his work might spark significant dialogue at dwelling. “The Twilight” earned him the one award ever acquired in Iran from the pre-eminent Fajr International Film Festival. However, as his unique tales started to take an more and more open place within the system, their public show was banned.

“I simply thought that I used to be a critic who might assist all the things get higher, that I might present by means of my movies what I noticed and that these in energy can be influenced by it and begin to change issues,” he recollects. “But as I received nearer to the tip of the movie, I spotted how naive I used to be, as a result of structural energy will be a lot stronger than particular person will.”

A line of dialogue from his 2011 drama “Goodbye,” about an Iranian lady determined to depart the nation, may very well be interpreted as Rasoulof’s personal sentiment: “When one is a stranger in a single’s personal nation, it’s higher to be a stranger in a international land.”

He tells me he would not determine with that impulse.

“My every day life was stuffed with empathy, as a result of I solely noticed (individuals) I had rigorously chosen,” Rasoulof says. «But I do know many individuals who, to make ends meet, can’t afford this luxurious. Therefore, their life is way more violent.”

“Being a gangster with some expertise since I’ve been in jail, I do know who I can speak to,” says Rasoulof, carrying his standing like a badge of honor.

(Jennifer McCord/For The Times)

Distrust among the many Iranian individuals, instilled by the regime, is a key tactic to keep up its grip. “It separates individuals, it destroys protest actions and it has no price to them,” “Sacred Fig” actress Maleki says by means of interpreter on a Zoom name along with her co-star Rostami.

Following the Mahsa Amini demonstrations, each actors – like their director, exiled in Europe – determined to now not participate in tasks that required them to put on the necessary Iranian hijab. “If I’m solely going to behave in a single film in my life, it higher be one thing I actually consider in,” provides Maleki.

Casting actors to make a movie in secret (on the threat of ending up in jail or worse) isn’t any trivial process. The methods he employs, Rasoulof says, are much like these employed by drug traffickers. “Of course, we had been simply smuggling human values,” he says half-jokingly, nonetheless amused at being put in that place.

First one in every of his colleagues would cellphone a possible performer and take his temperature saying: “We are engaged on this quick movie and a few points is not going to be fully compliant. If you take part, you could be a bit harassed. What do you assume?” They would proceed primarily based on their response. Rasoulof grew to become superb at figuring out fellow freethinkers.

“Being a gangster with some expertise, since I’ve been in jail, I do know who I can speak to,” he says, relishing his provocative standing.

I say it is endearing that he is in a position to extract humor from these ordeals. “There isn’t any different means ahead,” Rasoulof responds.

Even as soon as the individuals had been vetted and introduced into the venture, the manufacturing could not let its guard down. “Setareh and I learn the script earlier than we began filming, however on account of safety circumstances, we weren’t allowed to take it dwelling with us, ever,” recollects Rostami.

“Two individuals who ultimately joined the crew instructed me that they initially thought (the movie) was a ruse devised by the regime to seek out out who wished to work in underground cinema,” Rasoulof recollects. “Then my negotiator instructed me he did not belief those self same two crew members. He thought we should not carry them ahead as a result of They They had been a threat.”

Loyalty was key. A loyal one that did not but know precisely what he was doing was extra useful than an skilled skilled he could not belief. While Rasoulof admits he has needed to sacrifice inventive high quality at instances, he’s keen to pay that value.

“Being in a position to deflect censorship has its worth,” he says. “I had two selections: both to not make movies, as a result of I had little interest in making them below the dictates of censorship, or to make movies on this means.”

Rasoulof has little question that his movie, which received a particular jury prize at Cannes, will attain Iranian audiences by means of social media apps like Telegram. He encourages it, however dislikes the best way it’s projected. “I simply ask individuals to not watch it on their cellphone, however to ensure you have a pleasant, huge display you may watch it on,” he says, smiling.

Regarding the latest US presidential election, Rasoulof says that, at the least right here, individuals have “the selection to decide on this darkish time, so long as those that select the darkish time are the bulk, nevertheless small.”

In Iran, against this, a small minority has taken the complete nation hostage, leaving the inhabitants “no selection whether or not or not to decide on their very own darkness.”

The excellent news for Americans, in his view, is that the Trump administration will hopefully final solely a restricted time, and there nonetheless stays the opportunity of making higher selections sooner or later. This proper to self-determination and to vary or make errors is absent in Iran.

“For Iranians proper now, the one hope is that one other energy may also help us from exterior,” he says. “Because the Islamic Republic, initially, represses its personal individuals.”

During this unsure chapter of his life – doing interviews in Hollywood as a fugitive – Rasoulof basks in a newfound normality he is by no means encountered earlier than, derived from seemingly insignificant issues.

“In Iran, each time I used to be about to open the door to depart the home, I took a deep breath and thought, ‘There may very well be individuals exterior who might take you away,’” he recollects. “Now I haven’t got to fret about that once I open the door, and that provides me nice pleasure.”

That sense of safety, nevertheless, comes at a fantastic emotional price, acquainted to anybody who has been uprooted from a spot they as soon as knew. “I like Iran and its tradition,” he says. “That is the place the place I realized about life, the place I understood what humanity means. It’s the window I’ve been given into the world.”

Far from their dwelling nation, Rasoulof’s brave artists discover solace in one another, clinging to hope for a brand new daybreak in Iran.

“For me, dwelling now means being collectively in solidarity as human beings and never leaving one another alone,” Maleki says, wiping tears from his face. “For me, dwelling means having the ability to textual content somebody and say, ‘Come and have tea with me.’”

In the world that Rasoulof believes nonetheless exists, that invitation will at some point carry them again to Iran.