Sitting round a desk with actors Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley and writer-director Coralie Fargeat virtually appears like remedy — if folks had group remedy surrounded by publicists in an upscale London resort.

“The Substance,” Fargeat’s follow-up to her 2017 debut function, “Revenge,” is a blood-soaked body-horror movie that cleverly confronts ageing in Hollywood. Provocative and specific, the film (in theaters Sept. 20) upended a considerably snoozy Cannes Film Festival with an undercutting and sometimes satirical humorousness. It’s the identical sensibility that pervades our four-way dialog on the Corinthia Hotel in late August, the place an outburst of laughter can lead instantly to an admission of lingering trauma or a groan-inducing reminiscence.

Even now, a yr after wrapping the film in Paris, Moore, 61, and Qualley, 29, are grappling with what they endured on set.

“To provide you with an concept of the depth, my first week that I really had off, the place it was simply Margaret working, I received shingles,” Moore says, virtually proudly, in her acquainted deep rasp. All three are glammed up following our picture shoot, however Qualley has kicked off her heels they usually have a cushty air amongst them, the best way you’d in the event you’ve been by one thing intense collectively.

“Oh, yeah, I had loopy pimples for a full, long-ass time,” Qualley jumps in.

“And I then misplaced, like, 20 kilos,” Moore provides. Fargeat simply smiles, seemingly with no guilt about placing them by their paces.

Even figuring out Moore’s signature turns — 1992’s “A Few Good Men” and the romantic “Ghost” reverse Patrick Swayze — and Qualley’s personal standout work in Quentin Tarantino’s “Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood” and the Emmy-nominated collection “Maid,” the director is aware of she’s pushed them to new heights. It was one thing each Moore and Qualley readily accepted, regardless of the challenges. (The efficiency is already gaining critical Oscar buzz for Moore.)

“You need to stroll away feeling that you just put all of it on the desk,” Moore says. “It referred to as for it and it’s what you wish to deliver to it.”

“It was just like the loopy lab of a professor,” says director Coralie Fargeat. “It was type of like inventing our personal approach of doing a movie.” Margaret Qualley, standing, and Demi Moore within the film “The Substance.”

(Christine Tamalet / Mubi)

In “The Substance,” Moore performs Elisabeth Sparkle, an Oscar-winning, Jane Fonda-esque TV health teacher who’s fired the day she turns 50. To us, she stays glamorous and delightful, however her profession worth has diminished with the years. At least in line with loudmouth studio head Harvey (Dennis Quaid), who unceremoniously dumps her whereas grotesquely consuming a bowl of cooked shrimp. Empty of objective and determined to strive something, Elisabeth pursues a mysterious back-alley miracle remedy that provides her a chance to unleash a youthful model of herself (Qualley), so long as she shares her time together with her youthful physique, switching off each week. This second self, birthed from Elisabeth’s backbone in true Cronenbergian style, dubs herself Sue and is employed by Harvey to headline a brand new present with considerably extra intercourse attraction.

It’s a searing have a look at Hollywood’s tendency to place an expiration date on all the things, particularly girls, however “The Substance” additionally got here from a private place for Fargeat, 48, who remembers struggling when she turned 40. She discovered herself consumed with miserable ideas about rising older, assuming she would grow to be invisible. Writing the movie was a “liberating gesture” in addition to a painful one, confronting these fears.

“I wished to get freed from that feeling as a result of I felt that it was one thing that was so highly effective and never solely linked with age,” the director says, Moore nodding in settlement. “At every age there’s something which you can really feel is improper with you — with the best way you look, with the best way you’re feeling.”

Fargeat’s exact script options little or no dialogue. Instead, it depends on the stylized visible impression of the storytelling, which devolves as Sue breaks the time-sharing rule (due to course she does), refusing to modify again after her allotted week. As a consequence, Elisabeth’s physique breaks down, turning into an increasing number of ugly, till Sue, in desperation, births a monster of her personal. Fargeat takes benefit of cringe-inducing closeups and graphic, uneasy violence to disclose Elisabeth’s complicity in her final downfall.

“That’s what makes it such a strong piece,” Moore acknowledges. “It’s actually what she’s doing to herself that’s most violent. … (The script) took one thing that could be a very internalized violence towards oneself and externalized it on this approach that enables the viewers to have slightly objectivity and to then actually see what we’re doing to ourselves by that harsh, fixed criticism and comparability.”

“I learn a tagline in an article concerning the movie not too long ago that mentioned, ‘Being a lady is physique horror,’” Fargeat provides. “The film will be scary on many ranges, however the first is about enjoying with the violence of what we do to our our bodies.”

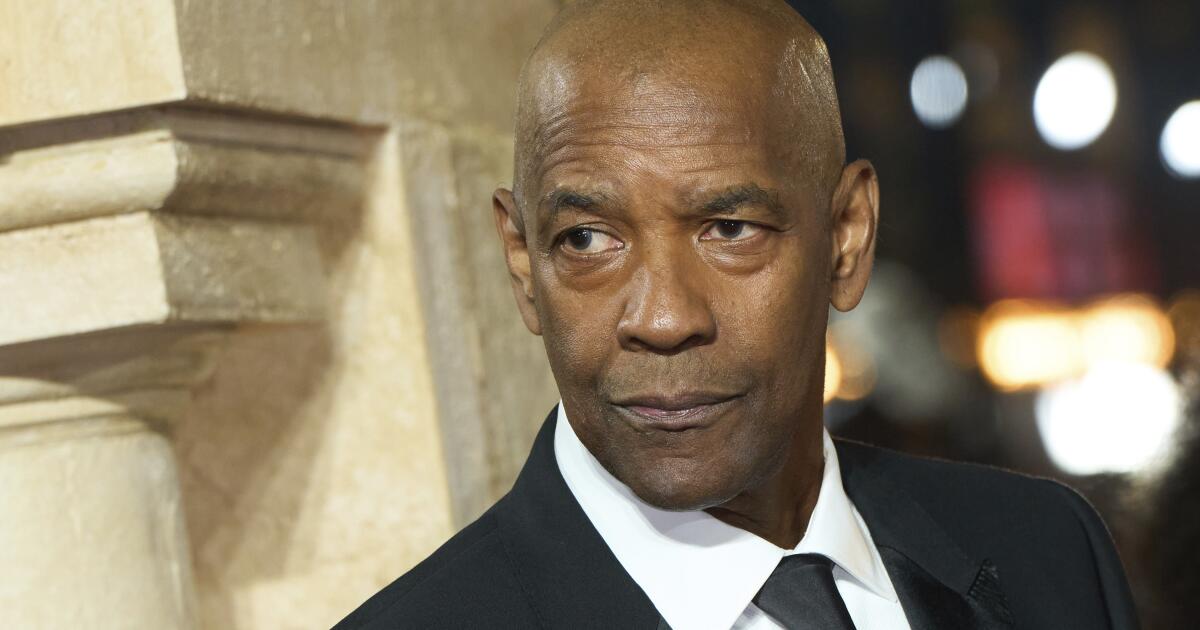

“We’ve really come an infinite distance,” says Moore, remembering her personal Hollywood experiences.

(Jennifer McCord / For The Times)

It’s inevitable that audiences will examine Moore together with her character, significantly as she herself has confronted sexism and ageism from her studios and producers, occasions she detailed in her notably frank 2019 memoir, “Inside Out.” But Moore says Elisabeth experiences the world from a really particular, self-destructive perspective.

“I feel from a human level, I relate, however I’m not Elisabeth,” Moore says. “There are totally different interpretations that she might have had in responding to (being fired), though we wouldn’t have had the identical film. Why didn’t Sue go, ‘I can run my very own present, I will be my very own producer’? Instead, she nonetheless seeks the identical validation, the identical approval.”

Sue represents an interpretation of the male gaze — the “male preferrred,” as Qualley places it. It was a part of what terrified her concerning the function: a hypersexualized character who exists primarily to suggest an unattainable preferrred. Qualley educated for months forward of final summer season’s manufacturing final summer season, lifting weights to get Sue’s seemingly flawless physique, which evokes what Fargeat calls a “shell” of basic feminine icons like Marilyn Monroe and Jessica Rabbit.

“We’re representing good, proper?” Qualley says. “And the film has a fairly impressed message. So I additionally thought it was vital for that good to be wholesome, even when it’s unrealistic. I’m lucky that the bare stuff was on the high as a result of all through the 5 months my ass was simply slowly deflating.”

Moore, unfazed by “The Substance’s” ample nudity, all of it motivated, quips, “I did admire how spherical Margaret’s ass was.”

Sue’s dance strikes proved tougher. Qualley is a educated dancer, however she wasn’t ready for a way it could really feel to embody full confidence in a scene the place she herself wasn’t. There was, in reality, “a lot crying” main as much as capturing Sue’s evocative dance quantity, a Dua Lipa-inspired, twerk-laden calisthenic writhing that wins her the present.

“We would simply go till I had a panic assault,” Qualley remembers of the “Substance” shoot.

(Jennifer McCord / For The Times)

“It’s extra of a problem than I spotted, pretending to really feel scorching whenever you don’t really feel scorching,” Qualley says, underscoring one of many movie’s central concepts. “I practiced that dance incessantly, on daily basis, till we shot it as a result of it’s thus far outdoors of the best way my physique strikes. But I actually loved pushing myself to determine it out.”

Qualley is conscious of how a lot Moore’s era, which additionally contains her mom, Andie MacDowell (each appeared in 1985’s “St. Elmo’s Fire”), paved the best way for her personal. She’s by no means performed a personality like Sue just because she’s all the time had extra choices.

“One of the explanation why this film was thrilling for me was as a result of I haven’t actually carried out one thing head-on like this the place the character is superficial and meant to be mega-hot,” Qualley says. “I’ve performed a bunch of f— freaks, so I think about myself fortunate.”

Ultimately, the most important hurdle for each performers was the unbelievable quantity of prosthetics within the movie, which had been created by French make-up artist Pierre Olivier Persin. He and Fargeat took inspiration from the movies of their youth, together with “The Fly,” “The Elephant Man” and “The Blob,” and Elisabeth’s eventual vacation spot — a devolution into Monstro, a horrific mashup of her and Sue — needed to be a real metamorphosis that fully distorted the character. Moore hunched herself beneath a layer of wrinkled pores and skin for the incarnation of Elisabeth that Fargeat lovingly calls Golem, whereas Qualley was tasked with turning into Monstro, a course of from which she nonetheless hasn’t recovered.

“I used to be in there, with (Demi’s) face plastered onto my very own physique,” Qualley says as Moore concurrently confirms, “I don’t suppose we might have match each of us within the go well with.”

Qualley jumps again in. “I want you had been in there with me!” she says, jolting straight up in her chair. “I used to be alone in that factor. I used to be working into issues. It was a torture chamber. The quantity of movies I’ve of me like, ‘I can’t do that anymore.’ It was eight days. I do know that doesn’t seem to be loads.”

Everyone within the room confirms that it does, really, seem to be loads.

Qualley, unpacking her trauma from the shoot, provides, “We would simply go till I had a panic assault. And the tempting factor is you wish to peel it off, however after all you may’t do this, since you’ll deliver your pores and skin with you.”

“I used to be in there, with (Demi’s) face plastered onto my very own physique,” says Qualley of the film’s unforgettable climax, a prosthetics triumph. Adds Moore, “I don’t suppose we might have match each of us within the go well with.”

(Jennifer McCord / For The Times)

There are a variety of memorably unsettling moments in “The Substance.” Body components drop off, pores and skin decays and there’s a deluge of blood so great it appears record-breaking. (That scene required 30,000 gallons of blood being sprayed from an precise firehose.) After Moore and Qualley wrapped 87 days of principal images at Paris’ Studios d’Epinay, the crew spent 30 extra days capturing the prosthetics for closeups.

“It was just like the loopy lab of a professor,” Fargeat says. “It was type of like inventing our personal approach of doing a movie.”

The most unsettling second within the film, arguably, comes courtesy of Quaid. His function, though small, is likely one of the most pivotal. The actor stepped in to switch Ray Liotta after the “Goodfellas” star’s loss of life. Quaid turned, Qualley notes, “the MVP.” As Fargeat places it, his character represents “all the dangerous behaviors in a single particular person.”

“By far essentially the most violent scene in your complete film is me having to take a seat throughout from Dennis Quaid consuming shrimp,” Moore says, laughing however clearly disgusted. “His mouth tearing off the heads — have a look at it. He’s illustrating precisely what he’s doing to folks. He’s ripping their heads off, tearing the tails off, spitting them out.”

“I need to say I used to be shocked what that scene provoked,” Fargeat provides, referencing the screening at Cannes. “Many males didn’t like that scene throughout postproduction. It turned fairly highly effective in what it symbolized.”

Quaid’s aptly named Harvey is pure satire, however he additionally stands in for all studio executives who deal with girls like objects.

“In actual life, it may be introduced barely extra subtly, however the undertone, the vitality, the intentionality is on the market on this planet like that,” Moore confirms. She remembers a second on the set of “A Few Good Men” when Aaron Sorkin stood up for her to a studio exec who wished her character, a Navy lawyer, to sleep with Tom Cruise’s courtroom crusader. When advised no, the exec mentioned, “Well, then why did we rent Demi Moore?”

Qualley, left, Fargeat and Moore, photographed in London in August.

(Jennifer McCord / For The Times)

“I feel that it’s how they had been conditioned,” Moore continues, acknowledging that she doesn’t blame the person as a lot as she does the system. “It was part of the accepted conditioning — that after all that’s why they might have somebody like me there.”

It’s totally different now, she thinks, though change has come slowly. “We’ve really come an infinite distance,” Moore says, slowly and thoughtfully. It’s clearly one thing she’s thought of, however she’s extra reflective than indignant. “It doesn’t make it OK, however we are able to’t hit a hammer over it. We have to maneuver (ahead). It actually begins with us.”

As our hour-long remedy session involves an in depth, Qualley nonetheless can’t deliver herself to confess that the ultimate movie made all her struggling value it. But the method, as laborious because it was, felt genuinely liberating for her.

“In a really, earnestly constructive approach, ending the film did really feel like there’s a cause why I signed up to do that — like there was an itch I wanted to scratch,” she says. “I really feel a sure freedom having endured the expertise.”

Moore echoes that. “That deep reminder of appreciating who you’re, as you’re, the place you’re, simply resonated extra as the method went alongside,” she says. “And not simply the exterior. Really, all of these inside issues of who we’re that we frequently can overlook. And the journey of what it’s taken to get the place you’re.”

For Fargeat, breaking out in a giant approach, the catharsis of “The Substance” extends to each herself and to the viewer. “You’re having the film change you a similar approach you hope the film will change the individuals who (watch) it,” she says. “I felt very liberated and extra inclined to self-love.”

It’s a liberation the movie affords us too. Ideally, although, with much less blood.