You may be simply as shocked to discover a Werner Herzog cameo in Pamela Anderson’s breezy 2023 memoir “Love, Pamela” as you’ll be to see her in certainly one of her movies. However, a possible collaboration nearly occurred and the German creator gave the Canadian hottie some phrases of profession steering: Never audition: Resist administrators who see your worth.

And now, director Gia Coppola has built a dream character around Anderson and his megawatt smile. In “The Last Showgirl,” Anderson’s first solo film role since 1996 “Barb Wire,” she plays Shelly, a veteran Las Vegas dancer accustomed to being a sex symbol. It’s part of the current enthusiasm for films that erect a fragile hall of mirrors around a female icon to reflect how pop culture has warped their image. (See also “The Substance,” elevated to an awards contender solely on the strength of Demi Moore’s backbone.) But this is not a bloody denunciation of the world of entertainment: it is a diaphanous portrait of a woman who, like Anderson herself , spreads through life like a marabou feather. It’s less a story than an atmosphere.

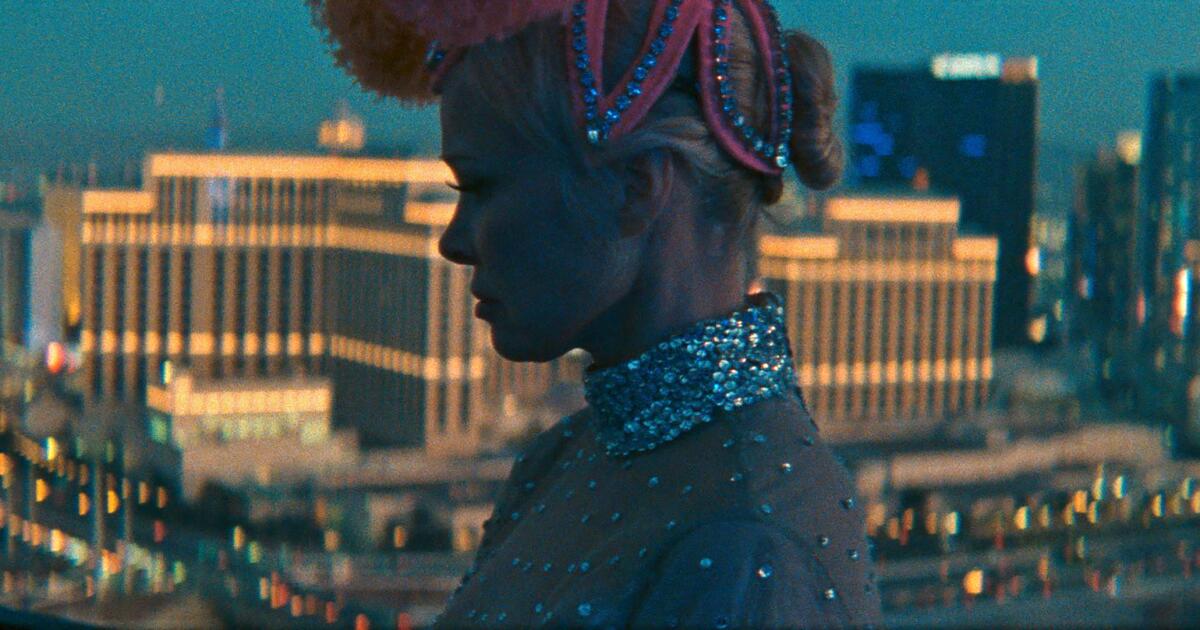

Coppola recently called Anderson the “Marilyn (Monroe) of our time” for her intellectual curiosity. Anderson may have grown up culture-hungry in rural British Columbia, but she feasted on French New Wave whenever she could, and here she does a great job of acting as if she were herself in a Godard film, piling her hair up in top of her Brigitte Bardot head and looking, presumably, at the half-scale Eiffel Tower in Las Vegas while we stare at it and hope things work out. Shelly, who speaks in a heightened version of Anderson’s whispered coo, is a fellow Francophile. For her, her long-running gig at Razzle Dazzle isn’t just a tacky nude show: it’s “the last descendant of Parisian Lido culture.”

Everyone else in Shelly’s orbit thinks the Razzle Dazzle AND a tasteless nude show, including her daughter Hannah (Billie Lourd), her theater producer Eddie (Dave Bautista) and her younger, more cynical colleagues Mary-Anne (Brenda Song) and Jodie (Kiernan Shipka).

We don’t see Shelly’s stage routine until the last sequence, so for most of the film we’re not sure who to believe. The scenes are livelier if you laugh at Shelly’s artistic ambitions. (When he insists that Razzle Dazzle’s charm is undeniable, Mary-Anne quips, “I could deny the charm.”) However, if you respect Shelly’s commitment, Kate Gersten’s screenplay becomes more interesting. The rhinestones are not diamonds, but still form a heavy crown.

Hollywood usually insists that people should follow their dreams: Shelly even gives this advice herself to Hannah, an aspiring photographer. But the film asks a follow-up question: even This crazy dream? Is it possible to see Anderson’s dazzling creation in pink and orange feathers as not only feminine but also feminist? It’s feminist to cheer, “You go girl!” like someone following their dream by throwing themselves off a cliff?

Autumn Durald Arkapaw’s cinematography looks at Shelly’s life the same way she does: what’s right in front is in focus, everything else is a blur. The truth is that Shelly can’t, or won’t, see her future beyond the stage. She’s naive, but she’s not a victim.

Coppola periodically reminds us that this darling can also be selfish, fickle and snobbish. The waitress isn’t for her, the adjacent sex circus is too low class and, as with the Rockettes, she finds all that football “very redundant”. Early on, Eddie announces over the loudspeakers that the casino’s new owners have decided to close the failing Razzle Dazzle in favor of something more fashionable. As Eddie delivers the bad news, the sound mix booms with a subtextual hum whoomp whoomp: Oops, Shelly missed the last helicopter out of Vietnam.

Anderson plays her real, as if perhaps he’d encountered variations of Shelly in Hugh Hefner’s cave. She has a self-awareness that allows her to be both sincere and feminine, while recognizing that outsiders might find Shelly synthetic. Her Shelly takes her version of reality seriously without expecting others to conform to her delusions. Even Shelly’s mundane moments come with a hint of the fantastic. Eating Chinese takeout with her daughter allows her to pretend she’s capable of having normal relationships, where her pastries aren’t the priority. In reality, Shelly can’t even get a date (and the only pretense of romance is forced).

No one is rooting for an industry that devours women. But what should we think of a woman who keeps throwing herself into the meat grinder expecting to be reborn as a filet mignon? A casting director (Jason Schwartzman) seems offended when Shelly tries to pass herself off as 36, about as long as she shines on the show.

At 85 minutes, “The Last Showgirl” can feel as padded as a push-up bra; is trying to convince us that this is an adult feature film. It lingers on shots of false eyelashes and foam rollers and slow-motion footage of Shelly posing on rooftops and traffic islands that becomes increasingly ethereal and ridiculous.

I like that Shelly treats the kaleidoscopic desert sun like a spotlight, but would she really drive to an empty gravel lot to pose for anyone? Some details feel wonderfully resonant, particularly the way Shelly never manages to remove every speck of glitter, or the way she keeps tearing off the wings of her costume like a cabaret Icarus. The film works hard to reiterate the fact that she is a woman out of time. His passion for black-and-white musicals is adorable, but his retro Walkman goes too far (as does the VCR in the break room at Razzle Dazzle).

But there is some truth to the idea that a person can freeze at the age when they felt safest. For Shelly, that means wearing acid-washed denim. Meanwhile, her older ex-colleague Annette (a dazed, scene-stealing Jamie Lee Curtis) sports frosted white lipstick and a hair color so bizarre you can’t imagine what was labeled on the drugstore box. (Gingerdead? Uselessness of strawberry?)

Curtis has some of my favorite lines in the movie (“What, you think I have a 501k?”) plus a great burlesque sequence where he impulsively climbs onto a platform and twirls to “Total Eclipse of the Heart” around a casino apathetic. crowd. It’s a long scene (you have to get your money’s worth from Bonnie Tyler) that goes on until the competing sounds and chimes of the gaming machines break the spell. You could turn his performance into a major Hollywood comedy and it would work just as well.

Only Anderson’s part, with all its confusing contradictions – neither comic nor tragic, neither pathetic nor heroic, neither subtle nor showy – seems to transcend. More than the film around her, Anderson earns our respect. For an encore, perhaps he will finally work with Herzog.

“The Last Showgirl”

Rated: R, for language and nudity

Running time: 1 hour and 25 minutes

Playing: Widely available on Friday 10 January